By Rae Martens (ferprogram.ca)

As I write this, I am currently flat on my back on the couch with my laptop propped up by my left hand and typing with my right hand. Some people might imagine such a position as being unproductive while writing. (It certainly is slower.) This is, however, how I move through getting things done like work or the odd Zoom call meeting. You get used to the idea of people looking at you from less than flattering angles. People almost always say, “You look so cozy!”, to which I always smile and crack a small joke in response. Some days this is the only way I can concentrate. Chronic dizziness deters me from being able to concentrate, let alone hold up my own head comfortably.

I’m also preparing a lecture for next week where I talk to emerging leaders in patient and family engagement. I look at my initial introduction slides and scan the all too familiar words, “transient aphasia”. Transient aphasia is a speech interruption that makes it difficult to find words, speak clearly, or understand language. It can also make it hard to read. Migraine auras sometimes make it feel like I left the house without remembering an otherwise natural process for me, spoken language. I provide a heads up that if I look confused and don’t say anything, I’ll provide a hand signal, and class will move to the discussion component. After, when my words return, I’ll send out a recording of what I was going to say.

I’m still kind of new at this neurological disability thing; it first occurred at a scientific conference. At the time, I wasn’t sure if I was having a stroke but thankfully that wasn’t the case. I’m slowly learning how to navigate the world with a diagnosis of vestibular migraine; that includes my time as a research partner. The choices I make when it comes to navigating the world affects my health baseline; and I like many other people with chronic illnesses are very protective of my baseline.

In a world where statements like, “Nothing about us, without us.” exists; a statement born out of protest. It’s a statement that didn’t come with conditions, or an asterisk with a caveat at the bottom in tiny lettering. Co-designing with people with lived experience demands working with who we are: and doing so accessibly. That includes the potential of inviting people with lived experience to attend conferences with you to present. How can we ensure that this time is a successful and safe one that continues to build trust and ensures they feel welcome?

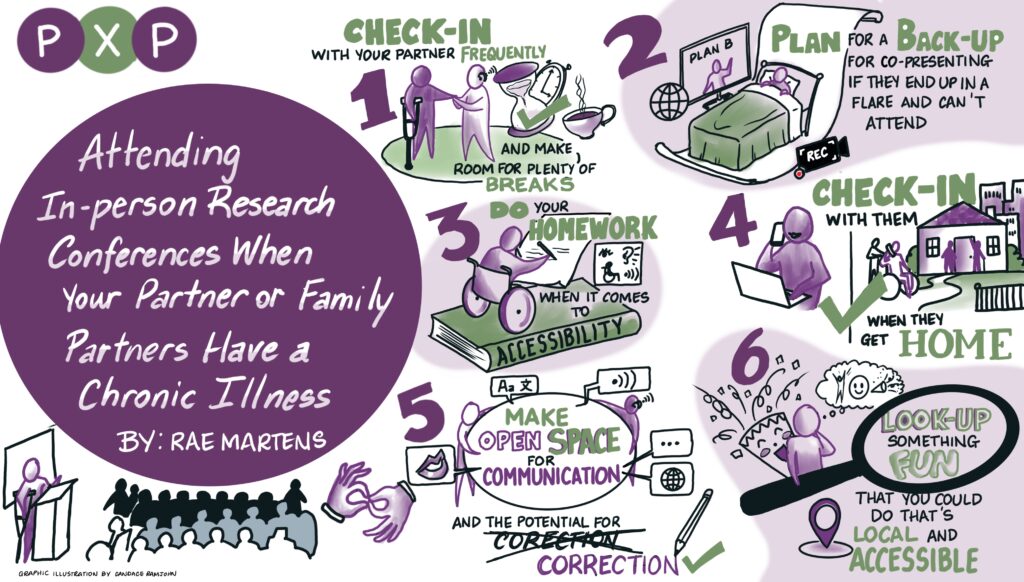

1) Check in with your partner frequently and make space for plenty of breaks. It’s difficult to provide examples that would be helpful across the board. I think an important consideration is to not be prescriptive about it. People with lived experience understand what they need. Designing a strategy with them before you leave can be a helpful way to start that conversation. You don’t necessarily need to be together the entire time. Having a way to communicate if they do need a hand for whatever reason can ensure they remain connected especially if there is an emergency. One example could be something like texting or using WhatsApp.

2) Plan a back-up for co-presenting if they end up in a flare and can’t attend. A laptop from bed is still co-presenting. Depending on what is available at the conference, you may wish to use Zoom or bring a videotape copy with you just in case that could be embedded in your slides. If you have internet access in site, it will help determine whether you use a web link or a video file.

3) Do your own homework when it comes to accessibility. Not all conference planners give this enough attention.

4) Check in with them when they get home. They know they’re planning for a recovery when they get home. This can help a person feel seen.

5) Make open space for communication and the potential for correction. You may mess up on occasion. Offer yourself some self-forgiveness and correct your course. Not every partner knows they are allowed to speak up as well. So sometimes it’s worth just saying it aloud so you’re both on the same page.

6) Look up something local and accessible that you could do to have some fun locally. If it’s a rough symptom day, even getting takeout and having dinner at the hotel offers opportunity to reflect on your time away.

For those of you reading this blog who are a patient or family partner: bringing someone with them to a conference may be a new experience for researchers. It may mean that you are the one to open the lines of communication about what you need. If you’re feeling up to giving travel to a conference a try for the first time, take moments to enjoy the experience where you can. Your voice matters in this space. Make accessible space in your heart to remember that.